"I will never let them take my dignity again."

Leon Weintraub was a prisoner in Auschwitz and survived – today he tells his story.

By Tobias Schreiner

Read the full story in German here.

This story has also been published in the German high school book "Geschichte und Geschehen Oberstufe" in 2015.

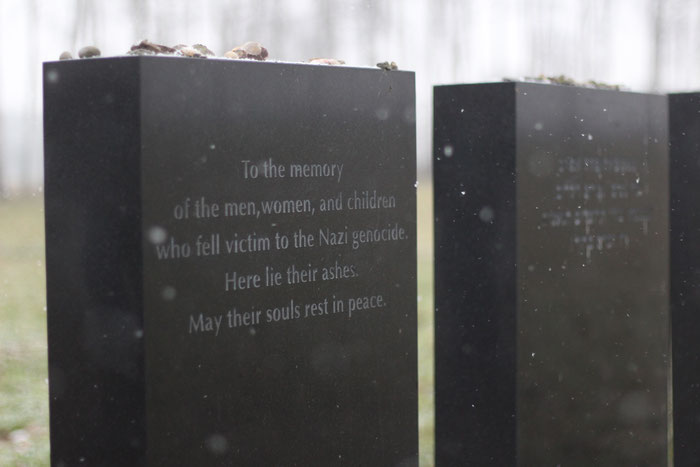

Oswięcim. Leon Weintraub looks up. He’s standing in front of a black tombstone with Hebrew characters. Small white flakes of snow are falling on the 89-year-old’s hair. “Once I was asked by a school class why they are building a memorial at the birth place of my mother. I said, we do not have graves for our beloved ones. The children laughed and were wondering that every dead recieves a grave. I told them: My mother who has been gassed and burnt here has turned to smoke like my relatives and left through the chimney. They do not have a grave. This stone shall substitute their sepulchre. Then they were silent.”

Weintraub’s gaze wanders along the former extermination facilities of the concentration camp Auschwitz II Birkenau. 70 years after the liberation of Auschwitz the survivor tells his story.

Leon Weintraub was born on 1 January 1926 in Poland. His father died when he was one and a half years old. His mother raised him together with his four older sisters in poor conditions in a tiny flat with only two rooms in Lodz. “School and books were places for me where I could escape from life at home”, he tells and his eyes turn glassy.

Aged 13, Weintraub was supposed to start grammar school. But when the Wehrmacht marched into Lodz in 1939, everything changed. “I can still remember the planes above our heads and the sound of the military boots on the cobblestones. The lines of the soldiers were insurmountable. They were spreading a force that would crush everything that might stand in their way.”

In winter 1939 Leon Weintraub and his family were resettled to Ghetto Litzmannstadt. In August 1944 the Ghetto got dispersed. Weintraub and his family were put on a train, crammed in cattle trucks with his mother, his aunt and two of his sisters. Southwards. For work, it was said. When the doors of the cattle trucks opened, hell awaited the young family.

Thousands of people were standing in line on “the ramp”. Hungry, exhausted and almost insane of fear. To their right the women’s camp, to their left the crematoria. Behind them the giant gate of the concentration camp Auschwitz Birkenau II, in front of them the screaming guards. The sweet smell of burned human flesh made Leon Weintraub’s blood run cold, holding the tiny backpack with all his goods and chattels tightly in his arms. “When I saw the barbed wire and the electric fences I knew: This is no place for the living but a place of death.”

It was on the “ramp” when Weintraub saw his mother for the very last time. “We will meet inside, she said. Because we thought that something had to continue inside”, he says and his voice starts to tremble. Finally Weintraub reached the end of the human line, standing in front of one of the camp’s doctors for selection. The doctor examined him, registered the 17-year-old as “able to work” and pointed his thumb to the right. Into the camp. Weintraub’s mother and aunt were not granted that chance. Examining them, the doctor pointed to the left. “Not able to work”. Gas chamber.

“We were not humans in Auschwitz. We were objects”, Weintraub says while standing in front of a cattle truck in the camp. They were eradicated like worthless objects. The biggest gas chamber in Birkenau was build to gas 1,600 people at once. Their corpses were burnt in the crematoria. Their ashes were raining from the sky day and night. “Auschwitz is the biggest graveyard in the world”, Krystyna Oleksy, former assistant manager of the memorial, reports. This is not meant metaphorically. The soil in Birkenau is saturated with the ashes of the murdered.

Leon Weintraub was sent to the “sauna”. The Nazis took all his belongings, he had to undress to get “desinfected”, washed and shaven. With corrosive chemicals they even got rid of his pubic hair. But the physical pain through the raw electric hair clippers and chemicals that were burning his skin were not the worst – it was the dehuminization, degradation. He was not a human being anymore. He was work force. A tool, that had to function until it broke.

Leon Weintraub does not tell a lot about his time in the camp. On cold, hard plank beds he lay squeezed together between other teenagers in Block 10. In a state of shock his perception was disturbed: “I could not think anymore, could not grasp a single clear thought. I was like in trance. My body was focussing on its basic functions.” Everyday life in the camp was wretched. As the other prisoners, the children were waiting for their allocation to other work camps. “It was a life of postponement”, he says.

One day Weintraub saw a group of naked figures standing between two baracks, supposed to be deported to another camp. Without knowing where they would be sent, Weintraub undressed in the shadow of a barack’s wall and hid among the group. This is how he escaped from the hell of Auschwitz. Centuries later he was told that Block 10, where he had slept with hundreds of other teens, was completely exterminated in the gas chambers only a few days later.

Weintraub was deported to Wüstegiersdorf and later to Dörnhau, where he had to do electric work. He survived the “death march” to Flossenbürg and other concentration camps and was put on a train 22 April 1945, heading towards Lake Constance. The train was supposed to sink in the lake with all its passengers. But due to an air raid the train had to stop. Weintraub escaped and was found the following night by French soldiers. He only weighed 35 kilograms, suffering typhus. Out of coincidence he heard that his sisters had survived Auschwitz and were freed after being deported to Bergen-Belsen.

Today Weintraub does not bear resentment towards Germans. “I cannot judge a whole nation. By such a generalization, that we Jews suffered ourselves, I would put myself on the same intellectual level as the Nazis.”, he explains. He has once and for all given up the role of the victim and admits: “I have hit another person with my fist in the face just three times in my life. These three were antisemites. I will never let them take my dignity again.”

If you liked this story, like and share it to keep the memory alive.

Info:

After the war, 1946, Leon Weintraub started studying medicine in Göttingen with just six years of primary school experience. In Göttingen he married a German girl – Katja Hof. She gave birth to their son two years later. In 1950 he returned to Poland to work in a women’s hospital in Warsaw. He wrote his dissertation 1966 and became a nationwide respected physician. But happiness as doctor, husband and father did not last for long. As a consequence of the returning antisemitism in Poland the government forbid Weintraub to continue his profession as a doctor in 1969.

Deeply ashamed to be excluded and persecuted by his own nation once again, Weintraub emigrated with his family to Sweden. His wife Katja died 1970 in Stockholm.There he started to work as a doctor again and met his later wife Evamaria. Together they are living in Stockholm until today. 2004 Weintraub recieved the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. He is father to three sons and one daughter.

I want to thank Dr. Leon Weintraub for sharing his experiences with me. For telling me about the worst happenings and the luckiest moments in his life. A big Thank You to Wolfgang Gerstner, Liliya Doroshchuk and the whole crew of Maximilian-Kolbe-Werk who organized the meeting between contemporary witnesses and young journalists in Oswięcim in January 2015. Without your spirit and commitment this piece would not have been possible.

Our journey is over – a new one begins

I tried to sum up my thoughts of my one-week-experience in Oswięcim.

The speed of the accelerating plane is pushing me deep into the soft bolster of my seat. The engines are howling, we gain speed. Slowly the plane is raising its nose to the sky and a dumb feeling in my stomach tells me that we’ve just left firm ground. We are flying. Rising higher and higher. Beneath us spread the fields and forrests of Poland white as ice. The closed cloud cover illuminates the scenery in a milky, grey light. Suddenly a glaring beam of sunlight breaks through the clouds and falls upon my face. The warming sun spreads trough the windows of the plane. Closely underneath us reaches an ocean of white-golden shiny cotton wool as far as the eye can see. We are on another journey again.

A journey home – away from the shadows of Auschwitz. Shocked, desperate by the cruelties we have seen and heard. But we return as richer beings. We are carrying a burden that is just a tiny piece of an inheritance we will never be able to fully grasp. The feelings and memories of Jacek Zieliniewicz, Zdzislawa Wlodarczyk and Leon Weintraub that we carry with us in our cameras and laptops are not easy to carry. It is a mission, a warning: “Now you understand what we experienced – do something with it.”

The knowlege that our reports and articles can only give small glimpses into the lifes of these valuable beings gives a bitter taste to it. A dull hole in our hearts. We can not completely conserve these memories. The gratefulness for what we were allowed to experience is overshadowed by the gigantic responsibility that lasts upon our shoulders. On the end of this journey we return as other persons than those we have been before. Our journey to Auschwitz is over. Now a new one begins.

How can we go on? How can we go back to our everyday life? How can we explain the incomprehensible? How can we put the inexpressible in words when those who survived the horrors of the Nazi extermination camps do not longer wander among us? How can we explain to our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren that there is a difference between killing and exterminating? That the fear of the unknown can lead to hatred that consumes everything? That doing nothing, nodding things through and ducking our heads must never, ever be an option? That law can be fertile ground for the worst possible injustice? That injustice must never be accepted? That stupidity and blind hatred sometimes deserve a fist in the face, as Mr. Weintraub said?

I don’t know. But I know one thing: We must try.

The following piece has a very important meaning to Leon Weintraub. He owns it in many different versions. This is his favorite: